An Intrasite Analysis of Agricultural Economy at Early Islamic Caesarea Maritima, Israel

Abstract

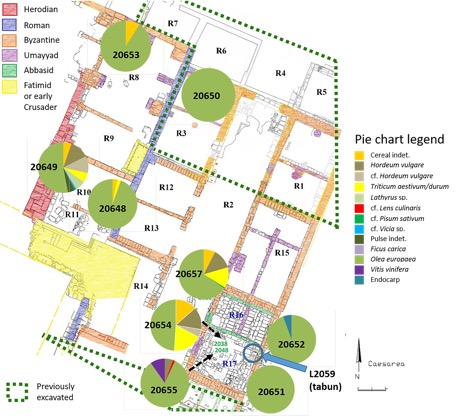

The archaeological site of Caesarea Maritima in modern-day Israel was an important coastal town in the Early Islamic period (c. 636–1100 CE). In this article, I analyze 15 samples of carbonized wood and non-wood macrobotanical remains recovered from two residential neighborhoods to investigate the production and consumption of agricultural plant products. The identified crop and wood taxa are typical for the Mediterranean coast. Wild seeds point to crop cultivation in the vicinity of the site. Plant remains were collected from discrete contexts and are interpreted with associated features and artifacts, revealing cereal processing debris across a series of rooms in a former warehouse. Such a socioeconomic shift in this building, from a storage area to a crop processing space, is detectable by combining this intrasite analysis with the diachronic research previously conducted at the site.

References

’Ad, U., Y. Arbel, and P. Gendelman. 2018. Caesarea, Area LL: Preliminary Report. Hadashot Arkheologiyot 130:1–13.

al-Muqaddasī. 1886. Description of Syria, Including Palestine. Translated by Guy LeStrange. Palestine Pilgrims’ Text Society, London.

Avni, G. 2014. The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach. Oxford University Press, New York.

Bouchaud, C., C. Newton, M. Van der Veen, and C. Vermeeren. 2018. Fuelwood and Wood Supplies in the Eastern Desert of Egypt during Roman Times. In The Eastern Desert of Egypt during the Greco-Roman Period: Archaeological Reports, edited by J. Brun, T. Faucher, B. Redon, and S. Sidebotham. Collège de France, Paris. DOI:10.4000/books.cdf.5237.

d’Alpoim Guedes, J., and R. Spengler. 2014. Sampling Strategies in Paleoethnobotanical Analysis. In Method and Theory in Paleoethnobotany, edited by J. M. Marston, J. d’Alpoim Guedes, and C. Warinner, pp. 77–94. University Press of Colorado, Boulder, CO.

Danin, A., and G. Orshan. 1999. Vegetation of Israel. Backhuys Publishers, Leiden, Netherlands.

Decker, M. J. 2009. Tilling the Hateful Earth: Agricultural Production and Trade in the Late Antique East. Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York.

Feinbrun-Dothan, N. 1978. Flora Palaestina. Part Three, Text. Ericaceae to Compositaceae. Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Jerusalem.

Feinbrun-Dothan, N. 1986. Flora Palaestina: Part Four. Text. Alismataceae to Orchidaceae. The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Jerusalem.

Gil, M. 1992. A History of Palestine, 634-1099. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Hillman, G. C. 1984. Interpretation of Archaeological Plant Remains: The Application of Ethnographic Models from Turkey. In Plants and Ancient Man: Studies in Paleoethnobotany, edited by W. van Zeist and W. A. Casparie, pp. 1–41. A. A. Balkema, Rotterdam, Netherlands.

Holum, K. 2014. The Archaeology of Caesarea Maritima. In Archaeology in the Land of “Tells and Ruins”: A History of Excavations in the Holy Land Inspired by the Photographs and Accounts of Leo Boer, edited by B. Wagemakers, pp. 183–199. Oxford books, Oxford.

Holum, K. G. 2011. Caesarea in Palestine: Shaping the Early Islamic Town. In Le Proche-Orient de Justinien Aux Abbassides: Peuplement et Dynamiques Spatiales, edited by M. D. Borrut, A. Papaconstantinou, D. Pieri, and J.-P. Sodini, pp. 169–186. Brepols Publishers, Turnhout, Belgium.

Jones, I. W. N., E. Ben-Yosef, B. Lorentzen, M. Najjar, and T. E. Levy. 2017. Khirbat Al-Mana‘iyya: An Early Islamic-Period Copper-Smelting Site in South-Eastern Wadi ‘Araba, Jordan. Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy 28:297–314. DOI:10.1111/aae.12096.

Kraemer, C. J. 1958. Excavations at Nessana, Volume 3: Non-Literary Papyri. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Liphschitz, N. 2007. Timber in Ancient Israel. Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv.

Patrich, J. 2011 Studies in the Archaeology and History of Caesarea Maritima: Caput Judaeae, Metropolis Palestinae. Brill, Leiden, Boston.

Ramsay, J., and K. Holum. 2015. An Archaeobotanical Analysis of the Islamic Period Occupation at Caesarea Maritima, Israel. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 24:655–671. DOI:10.1007/s00334-015-0519-x.

Ramsay, J., Y. Tepper, M. Weinstein-Evron, S. Aharonovich, N. Liphschitz, N. Marom, and G. Bar-Oz. 2016. For the Birds—An Environmental Archaeological Analysis of Byzantine Pigeon Towers at Shivta (Negev Desert, Israel). Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 9:718–727. DOI:10.1016/j.jasrep.2016.08.009.

Rowan, E. 2015. Olive Oil Pressing Waste as a Fuel Source in Antiquity. American Journal of Archaeology 119:465–482. DOI: 10.3764/aja.119.4.0465.

Stevens, C. J. 2003. An Investigation of Agricultural Consumption and Production Models for Prehistoric and Roman Britain. Environmental Archaeology 8:61–76.

Taxel, I., D. Sivan, R. Bookman, and J. Roskin. 2018. An Early Islamic Inter-Settlement Agroecosystem in the Coastal Sand of the Yavneh Dunefield, Israel. Journal of Field Archaeology 43:7, 551–569. DOI:10.1080/00934690.2018.1522189.

VanDerwarker, A. M., J. V. Alvarado, and P. Webb. 2014. Analysis and Interpretation of Intrasite Variability in Paleoethnobotanical Remains: A Consideration and Application of Methods at the Ravensford Site, North Carolina. In Method and Theory in Paleoethnobotany, edited by J. M. Marston, J. d’Alpoim Guedes, and C. Warinner, pp. 205–234. University Press of Colorado, Boulder, CO.

van der Veen, M. 2007. Formation Processes of Desiccated and Carbonized Plant Remains—The Identification of Routine Practice. Journal of Archaeological Science 34:968–990. DOI:10.1016/j.jas.2006.09.007.

van der Veen, M. 2011. Consumption, Trade and Innovation: Exploring the Botanical Remains from the Roman and Islamic Ports at Quseir Al-Qadim, Egypt. Africa Magna Verlag, Frankfurt.

White, C. E., and C. P. Shelton. 2014. Recovering Macrobotanical Remains: Current Methods and Techniques. In Method and Theory in Paleoethnobotany, edited by J. M. Marston, J. D’Alpoim Guedes, and C. Warinner, pp. 95–114. University Press of Colorado, Boulder, CO.

Zohary, M. 1966. Flora Palaestina: Part One, Text. Equisetaceae to Moringaceae. The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Jerusalem.

Zohary, M. 1987. Flora Palaestina: Part Two, Text. Plantaceae to Umbelliferae. Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Jerusalem.

Copyright (c) 2021 Kathleen M. Forste

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Authors who publish with this journal agree to the following terms:

- Authors retain ownership of the copyright for their content and grant Ethnobiology Letters (the “Journal”) and the Society of Ethnobiology right of first publication. Authors and the Journal agree that Ethnobiology Letters will publish the article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International Public License (CC BY-NC 4.0), which permits others to use, distribute, and reproduce the work non-commercially, provided the work's authorship and initial publication in this journal are properly cited.

- Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the journal's published version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgement of its initial publication in this journal.

For any reuse or redistribution of a work, users must make clear the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International Public License (CC BY-NC 4.0).

In publishing with Ethnobiology Letters corresponding authors certify that they are authorized by their co-authors to enter into these arrangements. They warrant, on behalf of themselves and their co-authors, that the content is original, has not been formally published, is not under consideration, and does not infringe any existing copyright or any other third party rights. They further warrant that the material contains no matter that is scandalous, obscene, libelous, or otherwise contrary to the law.

Corresponding authors will be given an opportunity to read and correct edited proofs, but if they fail to return such corrections by the date set by the editors, production and publication may proceed without the authors’ approval of the edited proofs.